reprinted with permission from www.workinprogressinprogress.com

Give us your elevator pitch: what’s your book about in 2-3 sentences?

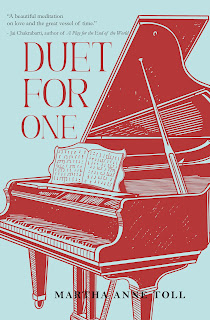

Duet for One is a lush and rewarding love story that follows the journey from grief to love within the world of classical music.

Which character did you most enjoy creating? Why? And which character gave you the most trouble, and why?

I most enjoyed creating three members of the supporting cast. The first is Thaddeus, a cellist who looks and sounds more like a lumberjack. Thaddeus is a person who calls it like it is. He’s an important counterweight to Adam Pearl, as Adam pushes through/and avoids grief following his mother’s death.

I also loved fleshing out Yvette, a professor of Caribbean studies at Penn who is humorous and grounded, in contrast to Dara’s tendencies toward seriousness and self-absorption. The same is true for Dara’s old friend Lydia, a fierce pianist whose cynicism masks a compassionate person whose life is filled with struggle.

I have worked hard to bring Adam Pearl to the page. Over time, as he’s moved to center stage, it’s been a challenge to render him with nuance. He’s a gifted violinist, who needs to know himself a lot better. He can be angsty but also kind and generous. He’s conflicted, like all of us.

Tell us a bit about the highs and lows of your book’s road to publication.

This book took twenty years to get born. There were a lot of lows. Too many rejections to count, including an agent in the distant past. Highs include my yearly revision of Duet for One, a book that is close to my heart and that has grown and thickened with time. Another high has been trying to render music on the page, which will always be a failing proposition, but brings me great joy!

What’s your favorite piece of writing advice?

Get your tush in the chair and ignore all writing advice.

My favorite writing advice is “write until something surprises you.” What surprised you in the writing of this book?

I don’t know if it counts as a surprise, but if you would have told me in 2004 that this book was going to be published in twenty years, I would have been surprised on all fronts—that it was getting published and that it would take so long!

How do you approach revision?

For me, revision is the heart of writing. Everything happens there. I revise a lot as I am in process. I do multiple entire-book revisions where I review character arcs, nuance, interior life, plot, dialogue, and structure structure structure. My last revision is the one where I put every word under a microscope to ensure it has a purpose. Otherwise, that word has to go!