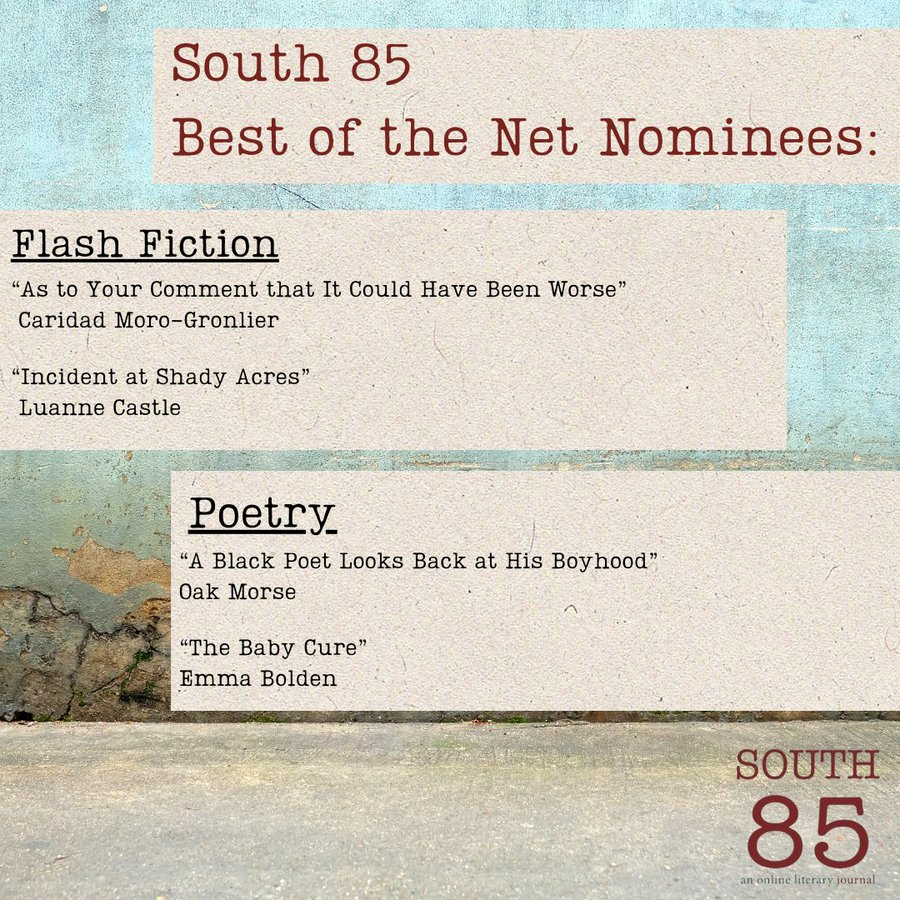

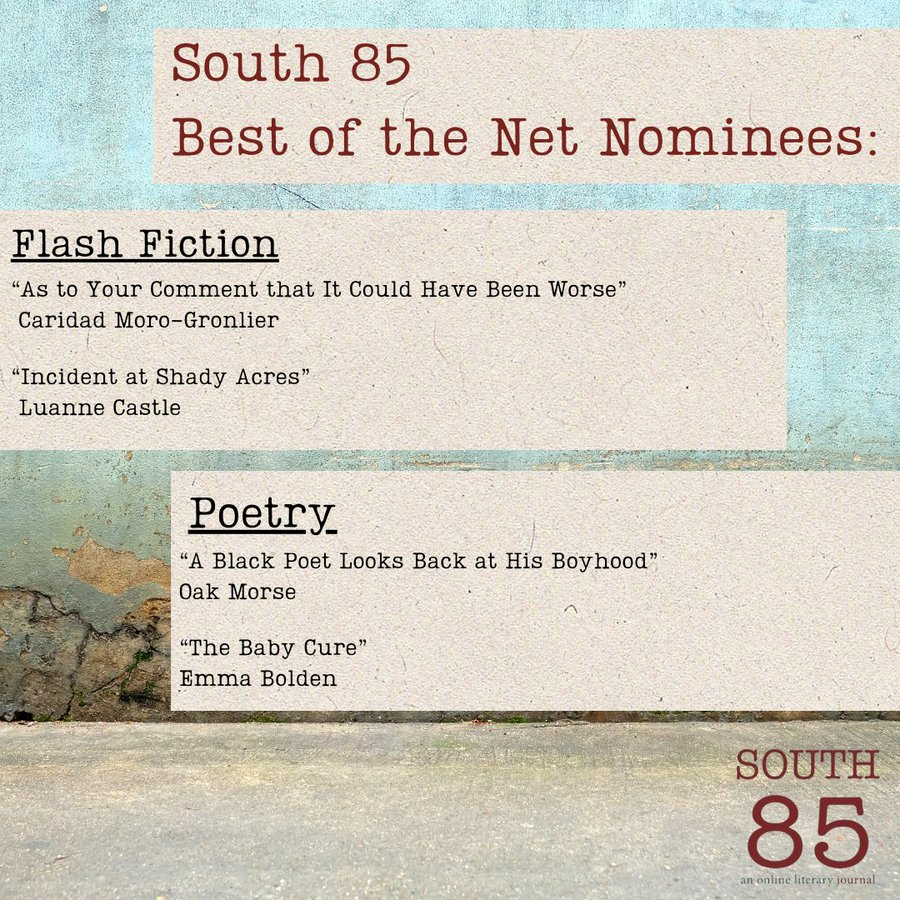

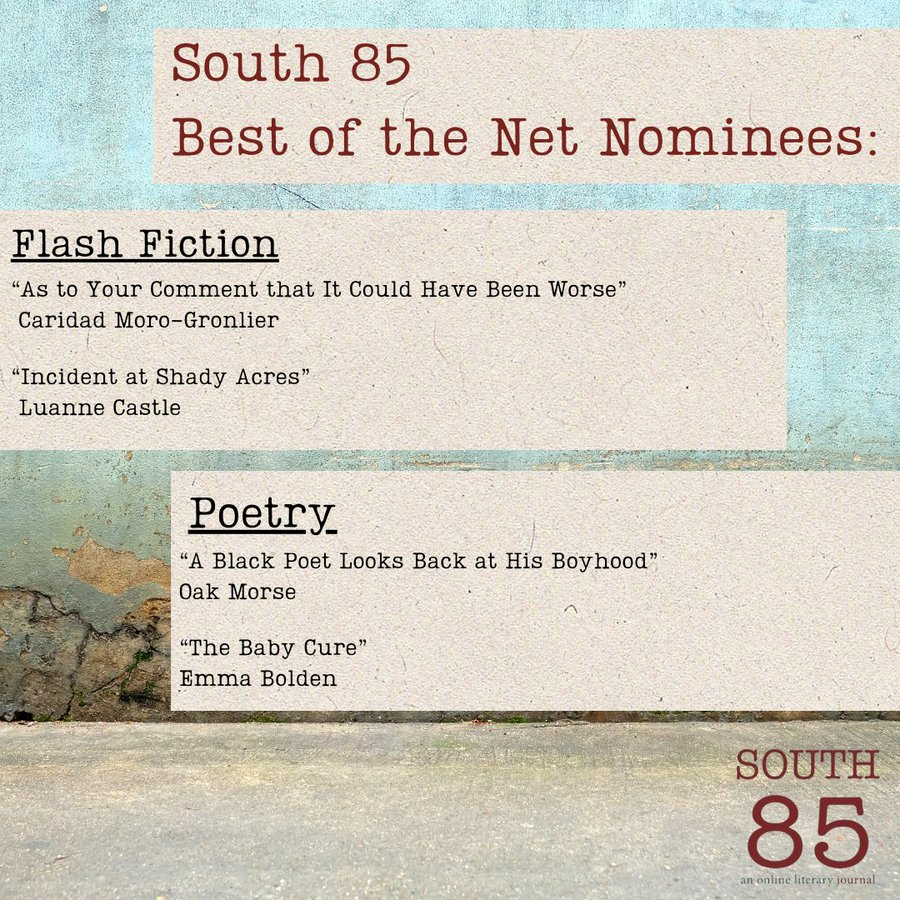

Best of the Net Nominations

“Yellow Bird” by Shannon Bowring (flash fiction)

“Paraiso” by Donna Obeid (flash fiction)

“El Roca” by Hayley Nivelle (flash fiction)

“Feathers and Wedges” by Karen Kilcup (poetry)

“Elixir for Knowing When to Surrender” by Katherine Seluja (poetry)

“If I get Alzheimer’s – Instructions for my Wife” by Justin Hunt (poetry)

Ezra Koch

“I don’t want a drink,” Camille repeated.

“Suit yourself,” Ernest said, and walked the short distance from the couch to the fridge shakily, his high bony hips jimmying side-to-side.

Camille felt nauseous. She didn’t ordinarily get motion sickness, but then, this wasn’t exactly ordinary.

“Can’t believe they let us,” Ernest said, looking out the window, a can of beer sweating in his hand. Telephone poles ticked past. “Ain’t it something?”

Her husband’s eyes flashed with the passing landscape. There was something so vulnerable, yet so hopeful, about his face when they moved, that she found herself falling in love with him all over again, against her better judgment.

“Yeah, babe. It sure is.”

They’d bought the mobile home five years back when a big deal had worked out. Since then Ern’d stopped selling, so he said, but not before getting half his teeth knocked out when a deal went sour. Still, she was glad they’d had the money—the freedom the mobile home had given them had proved necessary. Sure, it was a production—loading the house on the back of a tractor-trailer, the wide-load convoy, taping things up, tying things down—but once you got where you were going there was no unpacking. Everything was right where it always was. They’d moved three times since buying the home, but this was the first time Ernest had been able to convince the movers to let them stay in the house during the drive.

Camille came to stand next to Ernest and draped her arms around him.

“Do you think we’ll like, what is it… Manorville?”

“Gotta be better than Brookhaven.”

Camille bit her tongue. A few months ago he’d said Brookhaven would have to be better than Knox. They hadn’t been run out of town or anything, but she doubted anyone was sorry to see them go. Ernest had lost his job—showed up late and hung-over one too many times—and had already gained too bad a reputation to find another. At least this time it hadn’t been her fault. The time before it had, she admitted, yes, it had, but she didn’t like to think about that, her fear and her shame, what Ernest had done to that poor boy. They’d recovered. It wasn’t as if he’d never cheated, after all. They’d forgiven each other and moved a hundred miles south.

Outside, a barbed wire fence blurred before a range of rolling green hills. Black heifers appeared here and there like brail messages written in the landscape. They just hadn’t hit their stride yet. She’d let herself forget how much she loved this side of him—so brave and optimistic, all of his best qualities shining through. His last job had been below him. All his jobs had. She held the name on her tongue: Manorville. Things would be different there. They went around a turn and the house leaned and she gripped Ernest’s arm and his beer fell to the floor.

“Dammit, Cam,” Ernest said, wobbling back to the fridge. A goat, she thought with amusement, watching his bony strut, that’s what he looks like, a damn billy goat. The house rocked back and forth, settling. Camille grabbed paper towels and wiped up the spilled beer, on her hands and knees. They hit a bump and the whole floor bucked and her stomach lurched.

“I’m gonna be sick,” she said, and rose shakily, steadying herself against the wall as she walked to the bathroom.

“Shoulda had a drink,” Ern said.

She sat on the on the bathroom floor, resting her head against the cool porcelain, feeling ridiculous. Relief wouldn’t come. If she could just throw up, get it all out, she knew she’d feel better. She moaned and stretched flat on her back. She wished they would get there. How long did the movers, laughing at them, say the trip would take? A fresh start. She couldn’t wait to get to Manorville.

Lying on her back, staring at the off-white ceiling, she realized the mold was back. Little black spots spread from the corners, gathering in places unseen. She’d been battling that mold since they bought the house.

“You almost done?” Ernest yelled, banging on the door.

Camille didn’t move, didn’t make a sound. She couldn’t believe the mold was back. She’d tried everything she could think of short of ripping the ceiling apart: bleach, sprays, airing-out the bathroom for days at a time.

“Okay in there?”

She could not goddamn believe that fucking mold was back.

“Alright then,” Ernest said. She heard his footsteps retreat and suddenly began to feel better. As for the mold—she’d find a way to get rid of it. It was just mold, after all. She obviously wasn’t going to toss her cookies; she should really let him use the toilet. She hauled herself up.

“It’s all yours,” she said, stepping out of the bathroom. “Ern?”

She staggered into the living room and saw her husband illuminated in the open doorway, bony hips thrust forward, pissing into the ever-changing landscape.

Ezra Koch recently relocated to Portland, Maine, with his wife, daughter, and son, after living as a guitar maker in Santa Cruz, California for a decade. He has an MFA from the University of San Francisco and has been published as a poet and journalist. His debut novel, The World Belongs to the Askers, is being represented by Trident Media Group.

Ezra Koch recently relocated to Portland, Maine, with his wife, daughter, and son, after living as a guitar maker in Santa Cruz, California for a decade. He has an MFA from the University of San Francisco and has been published as a poet and journalist. His debut novel, The World Belongs to the Askers, is being represented by Trident Media Group.

Featured Image Credit: Photo by Lawton Cook on Unsplash

Mami is not religious. Fact is, I never even heard her say the word “God” not followed by “damn.” So when she jumps out of her chair praising Jesus, tears rolling down her face, I nearly spill my beer down my blouse. There she is on her knees, praying like a Pentecostal, arms in the air, swaying, the whole deal.

Then I see it. The face of Jesus on the window shade. Our very own Shroud of Turin.

I start to pull down the shade to get a closer look, but Mami lunges forward on her knees, all two hundred pounds of her, and grabs my sweater, wailing half in Spanish, half in English, saying only the pure of heart can touch Jesus.

“Well, then, José the maintenance man must be a saint,” I say, “He fixed that shade last week.”

Mami pounds her chest, and begs God to forgive me.

“Sarita, Jesus loves you.”

Yeah. Right. If he loved me, Tonio would still be alive. We’d still be living above the pizzeria on the avenue. I would be a medical assistant, working in a doctor’s office, not cleaning up piss and spit and who knows what in a cheap motel downtown.

I put my arm around Mami, and to my surprise, she doesn’t shove me away.

“Mami, this has to be an optical illusion. A shadow. Dirt.”

Mami’s eyes never leave the window. I follow her gaze and he’s still there: the hair, the beard, the mournful eyes, the crown of thorns, in shades of gray to black on the shade with its years of nicotine and cooking grease stains. I half-expect to see his mouth start moving like some Saturday morning cartoon.

I go to the kitchen, and call my friend Lucrecia in 7D. She works for a chiropractor in Williamsburg. She’d know what to do.

“Lu, you gotta get down here. Jesus is in my window.”

I explain that Mommy Dearest has turned into Mother Theresa.

I pour my beer down the drain, and look out the kitchen window.

Pleasant View Houses. Yeah, right. The pastoral scene I see is a trashed-up, dirt lot that used to be a lawn, and beyond it, another bleak high-rise building, tattooed guys huddled in puffed-up jackets under the yellow light by the bench, passing around a joint, waiting to make a sale. It was under that light Tonio and I first kissed.

I jump when there’s pounding at my door. Lu barges in, followed by Chubby, her husband, and half the damn building.

Amelia Flores from 6E, sick with breast cancer; Mr. Wilson from 2D, the stink of whisky wafting off him; Ruby Daniels from 1G, whose son, Ty was killed in Afghanistan; Marta and her near-blind mother from 5D. Leesha from 4H sashays in, drenched in perfume, praising the Lord, swinging a bottle of wine.

They keep coming: Kia, the teenager from 3F, whose mother OD’d last year; Wayne, the high school basketball star; Buzz, one of the X-Boyz; Vinny and Joe from the candy store; Sasha from next door, rapping a prayer. Pilgrims, every one, kneeling before the shade, seeking hope, I imagined, a miracle, some kind of reassurance there’s more to life than this. The last place my neighbors are gonna find hope is in apartment 2B at Pleasant View Houses in Coney Island.

I watch Mami greet everyone, shaking their hands, praying and crying with them. Most of these people avoid her. Many are victims of her tirades.

I look at the shade and I dare Jesus to give me a sign.

Maybe it was a breeze from the open window.

Maybe someone jostled the lamp on the table.

Maybe I’m, looking for a miracle, too. But I swear I see Jesus glow, golden, warm, inviting.

Darlene Cah used to improvise on stage in New York. Now she improvises with words in North Carolina. Her stories have appeared in various journals including Smokelong Quarterly, Referential Magazine, Wilderness House Literary Review, and Red Earth Review. Among her awards is the 2018 Hub City/Emrys Writing Prize. She has an MFA in Creative Writing from Queens University of Charlotte.

Darlene Cah used to improvise on stage in New York. Now she improvises with words in North Carolina. Her stories have appeared in various journals including Smokelong Quarterly, Referential Magazine, Wilderness House Literary Review, and Red Earth Review. Among her awards is the 2018 Hub City/Emrys Writing Prize. She has an MFA in Creative Writing from Queens University of Charlotte.

Featured Image Credit: Photo by Jon Tyson on Unsplash

M E Fuller

Surface fog radiates from the cold whisper of icy water, calm beneath a layer of hovering warm air. A loon cries its lonesome call that belies the truth. There is a nest for the pair in that cove, not far from my porch-side perch.

I watch for the boat to reappear. I know he will not survive. But I watch, and I wait, all day. My legs stretch to reach the porch rail. With ankles crossed in colorful Nordic woolen socks, the chill is kept at bay. I am distracted by my coffee mug, out of reach, ice crystals forming in the bottom. I stole that mug from the local diner last week. I liked it. I took it. They billed me.

He won’t be back. I smile, close my eyes heavy from watching the horizon—an unbroken grey slate. I can hear his insults and I recoil against the image of his mocking sneer.

She’s lovely. She’s sexy. She’s compliant. His words burn.

I feel content, well-satisfied, knowing he’ll never mock me again. His body will languish in the cold waters. Fish will sidle into his clothing to nibble on this fresh feast. He will rot with time and water wear.

I wish I’d had the courage to murder him in public, but I am not brave. She will be blamed. I will be consoled.

Life is good.

M E Fuller has always imagined other worlds of thoughts and ways of being. Her writing, drawings, and paintings reflect these worlds of place and interaction. She has published flash fiction stories Crazy Dog, Winter 2016, “Shark Reef, A Literary Magazine,” and Abel March, in “Talking Stick 26, A Minnesota Literary Journal,” September 2017. Her short essay The Last Roll Call, appears in PHOTOWRITE 2018, collaborations between photographers and writers.

M E Fuller has always imagined other worlds of thoughts and ways of being. Her writing, drawings, and paintings reflect these worlds of place and interaction. She has published flash fiction stories Crazy Dog, Winter 2016, “Shark Reef, A Literary Magazine,” and Abel March, in “Talking Stick 26, A Minnesota Literary Journal,” September 2017. Her short essay The Last Roll Call, appears in PHOTOWRITE 2018, collaborations between photographers and writers.

Featured Image Credit: Photo by Zoe Deal on Unsplash