Review by Christine Schott

Carmen Maria Machado may not be writing into a void, but it’s a space so sparsely populated with similar books that she might as well be. We’ve read about domestic abuse, and we’ve read about queer relationships, but rarely have we read about them together. Machado’s memoir of surviving verbal and emotional abuse by her unnamed girlfriend explicitly sets out to fill what she calls the “archival silence” around abuse in queer relationships. This mission in itself would make her history well worth reading, but it is her artistic approach, perfectly attuned to the challenges of the story she tells, that perhaps most distinguishes this unique and compelling work.

Carmen Maria Machado may not be writing into a void, but it’s a space so sparsely populated with similar books that she might as well be. We’ve read about domestic abuse, and we’ve read about queer relationships, but rarely have we read about them together. Machado’s memoir of surviving verbal and emotional abuse by her unnamed girlfriend explicitly sets out to fill what she calls the “archival silence” around abuse in queer relationships. This mission in itself would make her history well worth reading, but it is her artistic approach, perfectly attuned to the challenges of the story she tells, that perhaps most distinguishes this unique and compelling work.

Machado structures her narrative in the form of short, dazzling chapters, many of which could stand on their own as flash essays. Each is named with a guiding motif: “Dream House as Picaresque,” “Dream House as Shipwreck.” The relationship between title and content is difficult to pin down, as it varies chapter to chapter: often, the chapter imitates the form of the genre the title invokes, as though Machado had given herself a writing prompt: “Write your scene as a picaresque.” In others, the content resists or undermines the cheery expectations set by the title: in “Dream House as Stoner Comedy,” Machado recounts her girlfriend pressuring her into smoking pot to the point of incoherence, and though there is a tinge of humor (“Mozzarella is basically water cheese,” Machado observes to herself), it is more than counterbalanced by the tension and threat in the air around the girlfriend.

Related to the chapter titles are the running footnotes throughout the book, most of which connect elements of Machado’s experience to known fairytale motifs. For instance, when the girlfriend threatens both their lives by reckless driving in the middle of the night, Machado footnotes the folklore taboo of “doing thing[s] after sunset.” These recurring footnotes create a powerful undercurrent throughout the memoir that constantly reminds readers of the difficulty Machado faces in telling her story: it is at once individual and completely stereotypical. It is set apart from others in that a lesbian relationship is perceived differently by broader American culture, even now: some observers still refuse to see it as a real relationship; others still can’t understand how lesbians can have sex, and hence how they can be sexually abusive; and at the other extreme, some are so blinded either by their sexism or, ironically, by their pro-LGBTQIA+ views that they can’t believe a woman, especially a queer woman, could be an abuser. Machado, then, felt very alone in her suffering. But on the other hand, all abuse victims feel alone, regardless of the sex and gender of the parties involved, and everything the girlfriend does is something we’ve seen or read about men doing to women a hundred times over: isolating them, accusing them of infidelity, gaslighting them, swinging at random from extreme affection to extreme abuse. The footnotes connecting real events to fairytale motifs remind us that this is, in a very sad way, a story we’ve seen often before.

The other way Machado navigates between the two poles of uniqueness and universality is by playing with perspective. All the chapters having to do with the abusive relationship are told in second person: “This is your first mistake that day.” “At the car, she tells you to let her drive.” Only scenes before and after the relationship are in first person. One reason for this shift is thematic: when the protagonist is “you,” she is not her own person: she is an object, not an agent, seeing herself through the eyes of her abuser. But the other effect is to ask readers to step into the place of the abuse victim: we are addressed directly by the text, told that this is happening to us, in the moment of reading. In this way, Machado takes an experience that may be foreign to many of her readers and asks them to make it their own.

The most effective use of this perspective, as well as the genre imitation, is the set of chapters called “Dream House as Choose Your Own Adventure.” In this episode, the girlfriend accuses Machado of keeping her up all night by moving in her sleep. Every possible response to this accusation leads to a separate page readers are instructed to turn to based on their choice: “If you apologize profusely, go to page 163.” Each leads to a slightly different dialogue but the exact same ending: the girlfriend says something horrible and demeaning and Machado is left feeling helpless. If readers turn to page 165, a page not listed in the options (which instruct readers to turn to page 164 or 166), they encounter a torrent of verbal abuse, channeling the voice of the girlfriend: “It is impossible to find your way here naturally; you can only do so by cheating. […] What kind of person are you? Are you a monster? You might be a monster.” However, if they turn to page 167, also falling between the listed options, there is a ray of hope, this time in Machado’s voice: “You flipped here because you got sick of the cycle. You wanted to get out. You’re smarter than me.”

Despite the sadness of that comment, Machado does escape her abuser, by the rather unexpected route of the girlfriend breaking off their relationship. Machado writes from the perspective of a survivor at some distance from her experiences, perhaps the only position from which one can write cogently about abuse, and her survival and ultimate happiness give us hope. But her memoir leaps constantly between genres: between tragedy and romance, between horror and coming-of-age story, and that vacillation reminds readers of the urgency of making abuse visible. Just because Machado survived doesn’t mean everyone will, and if there is a call to action for the reader at the end of this book, it is to be willing to see what our current cultural narratives haven’t yet given us tools to understand: queer relationships are different, and at the same time they’re just like all others. They can go right, but they can also go wrong.

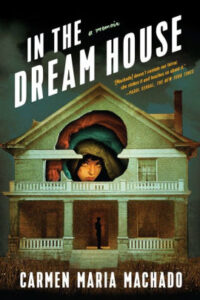

In the Dream House: A Memoir by Carmen Maria Machado

Graywolf Press. 2020. 265 pages, $26.00 [hardcover] ISBN: 1644450038

Christine Schott teaches medieval, world, and young adult literature at Erskine College. She holds a PhD in medieval literature from the University of Virginia and plans to graduate from Converse College with her MFA in creative writing in August 2020.

Christine Schott teaches medieval, world, and young adult literature at Erskine College. She holds a PhD in medieval literature from the University of Virginia and plans to graduate from Converse College with her MFA in creative writing in August 2020.