From her seat on the couch, with Carla either at her breast, on her lap, or in the bouncy seat in front of her, Ariel searched the streets and the fatal intersection for the blind woman. The winter was prolonged and bitter, and Ariel wondered if the blind woman preferred to remain indoors. But she feared the worst scenario. She feared it so much she didn’t want to confirm it by searching back issues of the Globe or Herald.

After three months, Ariel returned to the Boston Children’s Care Center. She and Summit employed a nanny from Ireland to look after Carla thirty hours a week. Summit continued his adjunct teaching at B.U. and gave a paper in late February in Baltimore at the American Philosophical Association’s regional conference. They hoped it would help him land a tenure-track job, but specialists in French existentialism weren’t being hired. Or at least Summit wasn’t. He had a single on-campus interview, at Penn State-Erie, from which he returned with bronchitis and no job offer. His spirits were as miserable as the March weather. In April, however, he gave a lecture entitled, “The Stranger: How Our Baby Nearly Killed Us and Why Camus is Laughing,” at the Serenade Coffee House. The twelve people who attended said they had never laughed so hard. Carla, defying everything Summit said, slept through it all.

A week later, on an April day in which bird songs overthrew the sounds of car engines and the air was filled with the scent of young flowers, Ariel was standing at the corner of Serenade and Division, with Carla in a BabyBjörn on her chest, when the blind woman stepped beside her. She had a guide dog, a male golden lab with brown eyes who seemed to wear a contented half smile. Carla squealed in delight—she loved all animals—and the blind woman, whose white hair, uncovered, was like a blazing comet, said, “She found a friend,” and Ariel said, “It seems so.” (Later, she would wonder how the blind woman knew Carla was a girl.)

“I have to tell you,” Ariel said to the blind woman, “the last time I saw you, you were headed into the middle of the street. There were cars coming, brakes shrieking. I thought for sure…well…”

“But you saw I survived,” the woman said, “albeit with a broken ankle.” (Only in Boston, Ariel thought, could one have a conversation in the street and hear the word “albeit.”)

“No, I…well…” And Ariel gave the woman the quick version of her labor, delivery, and first-two-weeks-with-Carla story.

“You had your own close call,” the woman said.

There was a silence before Ariel said, “You have a beautiful dog.”

“And you,” the woman said, “have a beautiful –”

But whatever she said next was lost in the sound of a car’s insistent horn. Ariel wanted to ask her to repeat herself, but presently the woman said goodbye and crossed the street. Ariel and Carla turned home.

Daughter? Ariel wondered.

Husband?

Friend?

Life?

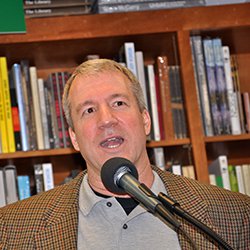

Mark Brazaitis is the author of seven books, including The River of Lost Voices: Stories from Guatemala, winner of the 1998 Iowa Short Fiction Award, The Incurables: Stories, winner of the 2012 Richard Sullivan Prize and the 2013 Devil’s Kitchen Reading Award in Prose, and Julia & Rodrigo, winner of the 2012 Gival Press Novel Award. His latest book, Truth Poker: Stories, won the 2014 Autumn House Press Fiction Competition. He wrote the script for the award-winning Peace Corps film How Far Are You Willing to Go to Make a Difference?

Mark Brazaitis is the author of seven books, including The River of Lost Voices: Stories from Guatemala, winner of the 1998 Iowa Short Fiction Award, The Incurables: Stories, winner of the 2012 Richard Sullivan Prize and the 2013 Devil’s Kitchen Reading Award in Prose, and Julia & Rodrigo, winner of the 2012 Gival Press Novel Award. His latest book, Truth Poker: Stories, won the 2014 Autumn House Press Fiction Competition. He wrote the script for the award-winning Peace Corps film How Far Are You Willing to Go to Make a Difference?