Chris Menezes

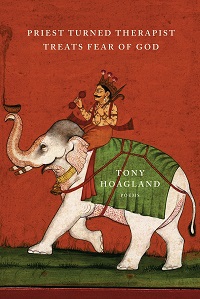

Tony Hoagland’s last book of poetry, Priest Turned Therapist Treats Fear of God, published in June of 2018, just four months before his death, explores the tangles of contemporary human experience that looks for beauty and happiness within the current American milieu of late stage capitalism, fraught with inequality and injustice. While there are no direct references to Hoagland’s illness within the book, we see a poet at the end of life trying to take it all in and make peace with everything–the good, the bad, and the messy. Rather than detangle the mess that life makes of emotion and thought—the highs, lows, monotonous loops and insane contradictions—Hoagland presses a finger on the common piece of thread that connects the entire ball of yarn. In tracing the pattern, he shows the intricate beauty behind the entanglement, enjoying every knot and twist. There is a certain powerlessness to Hoagland’s observations. This is not a book of answers, but a means to cope through laughter, connection found in brief everyday moments of shared relief, joy, and suffering. He does this through clear images, direct language that swings from elliptical fragmentation to narrative, blending everything we’ve come to love about Hoagland’s poetry—astute observation, humor, profound sadness and pleasure found in the most unlikely of places.

Tony Hoagland’s last book of poetry, Priest Turned Therapist Treats Fear of God, published in June of 2018, just four months before his death, explores the tangles of contemporary human experience that looks for beauty and happiness within the current American milieu of late stage capitalism, fraught with inequality and injustice. While there are no direct references to Hoagland’s illness within the book, we see a poet at the end of life trying to take it all in and make peace with everything–the good, the bad, and the messy. Rather than detangle the mess that life makes of emotion and thought—the highs, lows, monotonous loops and insane contradictions—Hoagland presses a finger on the common piece of thread that connects the entire ball of yarn. In tracing the pattern, he shows the intricate beauty behind the entanglement, enjoying every knot and twist. There is a certain powerlessness to Hoagland’s observations. This is not a book of answers, but a means to cope through laughter, connection found in brief everyday moments of shared relief, joy, and suffering. He does this through clear images, direct language that swings from elliptical fragmentation to narrative, blending everything we’ve come to love about Hoagland’s poetry—astute observation, humor, profound sadness and pleasure found in the most unlikely of places.

Divided into four sections of over sixty-five pages of poetry, Priest Turned Therapist Treats Fear of God begins with the poem “Entangle,” a perfect introduction to Hoagland’s motives, laying the foundation for what the reader can expect from the rest of the book. He begins, “Sometimes I prefer not to untangle it. / I prefer to remain disorganized.” Right away, Hoagland elevates the messy over the organized, imperfection over perfection. Although he starts with this entangled abstraction, he quickly puts feet and body to it by comparing it to a certain shrubbery he passes on Reba Street, offering a nice image that serves as both metaphor and visual aid for his abstract subject—society or life. Within his description of the shrubbery, Hoagland notes, “The white and purple combination of these species, / one seeming to possibly be strangling the other, / one possibly lifting the other up—it would take both a botanist and psychologist to figure it all out, / -but I prefer not to disentangle it.” Hoagland’s metaphor is not difficult to unravel, but rather, in classic Hoagland fashion, it’s clear, accessible, and clever as hell. He is not here to offer an answer or a reason to the complications of living, although we suspect that he could, and even says, “I could probably untangle it.” He would rather enjoy it:

yet I prefer to walk down Reba Street instead

in the sunlight and the wind, with no mastery

of my feelings or my thoughts,

purple and ivory and green, not understanding what I am

and yet in certain moments remembering, and bursting into tears,

somewhat confused as the vines run through me

and flower unexpectedly.

Hoagland writes with a keen awareness of his chosen aesthetic, moving from elliptical styles to traditional narratives, depending on his objective. The first elliptical poem in the book is found just five poems in, using fragmentation, humor, and abstraction. Hoagland writes about elliptical poetry quite a bit in his craft book, Real Sofistikation, often discussing the potential pitfalls and/or positives of the aesthetic compared to traditional narrative poetry. He addresses this very topic within his elliptical poem “Which Would You Prefer, A Story or an Explanation?” Hoagland gives us both, as the poem shifts to fragments of dialogue that jump in time and place, to observations to abstract ideas, like in the lines “I am interested, said Madeline, in people’s ability to live their lives / in fragments. Two ex-husbands, three jobs in seven years, one daughter, / a geranium, and a certain TV show,” and “The pursuit of happiness is a particularly American form of / nihilism,” and then “I can’t tell the difference between inner peace and mild depression, / writes her friend from Philadelphia, in small blue script / on the back of a postcard of Chagall.” Hoagland introduces us to Madeline as a character within the poem through snippets of dialogue and fragmented moments, teasing the narrative until he drops the plotline that could be her story: “In the next two years, Madeline will have a love affair, / visit Bali and return, develop endometrial cancer, / and reconnect with her childhood Catholic faith, / worth more to her than anything.” Hoagland then shifts away from the straight narrative of Madeline to end on a fragmented image that seems to serve as a metaphor for not only Madeline’s life, but all of ours: “Even at the bottom of self, even in the illness and despair; / in hubris, ecstasy and gloom, / the chick can be heard inside the shell, / pecking to get out. Pecking and pecking.” The reader is left to answer the question of the title for themselves; however, after navigating through Hoagland’s entanglement of elliptical and narrative devices, the answer seems to be both.

There are so many other great poems that are worth talking about in Priest Turned Therapist Treats Fear of God, but for the sake of brevity, I suggest you pick up a copy and read it for yourself. You will enjoy Hoagland’s social-political humor, like in the book’s title poem: “In Hollywood, fifty movie stars have pledged / not to use their swimming pools / until world thirst is ended;” his ability to capture moments of human honesty within clear images, like in the poem “Examples of Justice:” “when the attorney stands beside her car, / removes her sunglasses, and looks up at the sky;” and be comforted by a shared confusion and love for what is natural, like in “Hope:” “I didn’t belong in the Twenty-First Century. / I didn’t belong anywhere anymore. / I sat in my old-fashioned kitchen / staring at the green Formica counter. / That’s when the butterfly floated through the window, / and landed on the artificial flower.”

Chris Menezes holds an MFA in Poetry from Converse College. His work has appeared in journals like Pearl, Switchback, RipRap, Buck Off Magazine, Foliate Oak, Goldman Review and Best Emerging Poets of California. In addition to working as a freelance writer in California, he volunteers on the poetry committee of South 85 and Carve Magazine.

Chris Menezes holds an MFA in Poetry from Converse College. His work has appeared in journals like Pearl, Switchback, RipRap, Buck Off Magazine, Foliate Oak, Goldman Review and Best Emerging Poets of California. In addition to working as a freelance writer in California, he volunteers on the poetry committee of South 85 and Carve Magazine.