Amy Sawyer

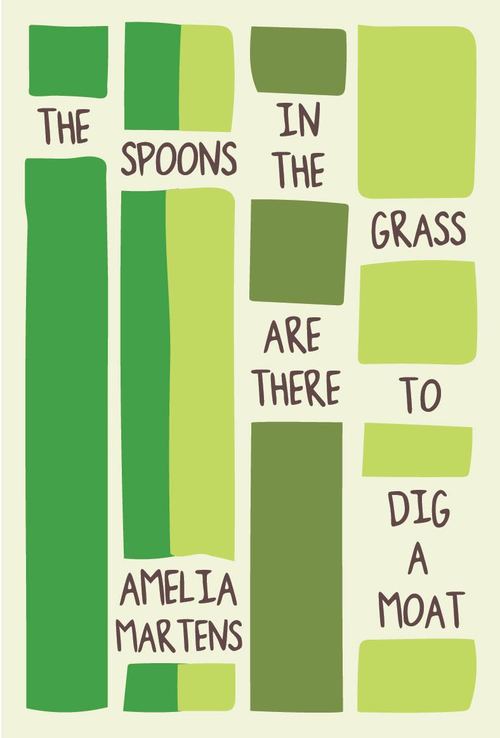

You’ll never read a more playful book of doomsday poems than Amelia Marten’s The Spoons in the Grass are There to Dig a Moat. Martens’ dark humor is delightfully paired with her astute observations of quiet pleasures. Her poems are grand with sweeping cosmic battles and frequent mentions of death and the end times, while also intricately small. In the poem “We Ask for Five Minutes,” she includes both the grandiose and the mundane as life’s simple pleasures are taken away, “At the end of the day, the peach always falls into the ocean and we’ve come too late to have anything to say.” From dying dogs to hydrogen bombs, the poet’s world is filled with impending doom. “Our daughter” mentioned throughout the poems inhabits the same world as skeletons, hunger strikes, and nuclear fallouts.

You’ll never read a more playful book of doomsday poems than Amelia Marten’s The Spoons in the Grass are There to Dig a Moat. Martens’ dark humor is delightfully paired with her astute observations of quiet pleasures. Her poems are grand with sweeping cosmic battles and frequent mentions of death and the end times, while also intricately small. In the poem “We Ask for Five Minutes,” she includes both the grandiose and the mundane as life’s simple pleasures are taken away, “At the end of the day, the peach always falls into the ocean and we’ve come too late to have anything to say.” From dying dogs to hydrogen bombs, the poet’s world is filled with impending doom. “Our daughter” mentioned throughout the poems inhabits the same world as skeletons, hunger strikes, and nuclear fallouts.

Her humor is often expressed when she uses Jesus as a recurrent character. Jesus works at a Drive-Thru in the poem “In God’s Country” where, “His window only opens halfway. But it’s enough space for Jesus to look drivers in the eye. Enough time to tell them he knows, they know, we’re all heading uphill to die.” A reader can delight in the painful comedy of Jesus handing over both “a grease-stained bag” and bleak pronouncements.

Using Jesus as a 21st century symbol, Martens humanizes the divine, yet retains an aura of his omniscience. Martens’ Jesus character is passive, a bumbling observer. He doesn’t interact much with the world and seems inept to solve its problems. In the poem “Tuesday” Jesus observes of destruction with “every bridge has been blown up. Cardboard castles burn down in the background” and yet he does nothing. It ends, “Sometimes no one says enough is enough; enough is too far away. Sometimes Jesus goes back to work, having forgotten what he was going to say.” When trading in cosmic language, the humanity of Martens’ Jesus pales in comparison to the cosmic battles.

Marten’s use of “our daughter” is more prophetic and powerful than her Jesus character. The personal connection to her real-life daughters makes the recurrent daughter seem more vibrant than the static Jesus. In the poem, “Pre-Alice” she recounts a series of questions from her daughter like “Why does the grass bleed on my feet? Does it scream?” She captures the prophetic voice with the line, “We watch from the far side of the parabola; it’s not all downhill from here, but it looks that way.” The child’s lens into the adult world is a refreshing touchstone throughout the book. The daughter’s voice isn’t childish or sentimental, but earnest with deep thoughts and questions. Shying away from clichés of parenting and childhood, the child’s perspective is an effective tool, offering insight that couldn’t be gained in another way.

While the book is composed entirely of prose poems, Martens never compromises finely-crafted language. The book is filled with hidden rhyme and assonance that begs for the poems to be read aloud like, “We need a bandage. We need an adage, an adverb, a mountain sage” or “We listen to our daughter cry while frogs uncork their throats. An owl in our oak hits each note necessary to pull a white mouse to the sky. If she needs to ask, then I need to tell her why.”

Amelia Martens’ imaginative book of poems will stick with you. She leaves room for the reader to be a fellow time-traveler as we approach what feels like World War III. It might be the end of times, but Martens is a great companion noting the moments of beauty and divine all around.

Amy Sawyer is a poet residing in Washington, DC. She studied philosophy and religion at Clemson University and earned her MFA at Converse College. Her poems have appeared in numerous journals, such as Mud Season Review, Stand Magazine, and South Carolina Review. She volunteers for PEN/Faulkner’s Writers in Schools program and manages the website allpoetryisprayer.com

Amy Sawyer is a poet residing in Washington, DC. She studied philosophy and religion at Clemson University and earned her MFA at Converse College. Her poems have appeared in numerous journals, such as Mud Season Review, Stand Magazine, and South Carolina Review. She volunteers for PEN/Faulkner’s Writers in Schools program and manages the website allpoetryisprayer.com