Jody Hobbs Hesler

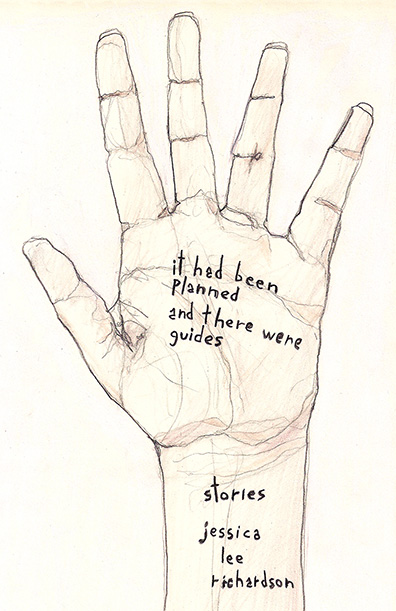

What experiment doesn’t Jessica Lee Richardson attempt in her story collection, It Had Been Planned and There Were Guides? There is nothing traditional here. Story structures, points-of-view, and subject matter all refract through Richardson’s creative lens. The collection is a riot of never-before-seen premises, an entertaining gallery of the bizarre.

What experiment doesn’t Jessica Lee Richardson attempt in her story collection, It Had Been Planned and There Were Guides? There is nothing traditional here. Story structures, points-of-view, and subject matter all refract through Richardson’s creative lens. The collection is a riot of never-before-seen premises, an entertaining gallery of the bizarre.

The stories in this collection contain unique, even outlandish, subject matter. In “Arrivederci,” an in-vitro monster rushes to share a lifetime of stories with a fetus before its birth. A grandmother befriends and communicates with a family of brown recluse spiders in “Not the Problem,” eventually preferring their company to her own granddaughter’s despite the spiders’ life-threatening habit of biting her when irritated. A factory workplace love affair seems to occur through the medium of proto-product plasma at one of the character’s work stations on an assembly line in “Basic Ten.” In “All She Had,” a woman’s diaphragm is inhabited by “a panel of grandfathers” who constantly criticize her. A few stories feature company software that appears almost sentient, and many deal with the strange alienation that seems to be a byproduct of our digital-communication-addicted culture.

Richardson also makes clever use of perspective. In “We Win,” for example, “we,” the project team members share the feats and struggles to develop a shark-resistant bodysuit with “you,” the presumed appreciator of said suit. The reader, then, takes part in the story both as a member of the “we” in the project team and as the “you” reading about their product, introducing intimacy and confusion into the story. Similarly, in “No Go,” email editing software appears to be relating the story, which unfolds as a series of onscreen messages among the user, the software as it makes suggestions, and the instant-message help line as the user experiences increasing frustration. Once again, the effect of perspective is an odd combination of immediacy and dislocation.

Clearly Richardson suffers no shortage of imagination, and her skill with language adds spice of its own. The moving landscape outside a train window in “Free Baby” is “the golden spray of industrial buildings” (39). In “Songbun Song,” privation is vividly animated in “Hunger will push a memory heavy as a freight train forward with one hand” (56). From “Even the Line,” we get a lovely reflection on mortality: “You were all fossils waiting to happen, fibers for the sky to rub down on, and that was fine” (179). As these examples suggest, Richardson’s language can be stark or elastic, sudden or gentle, as the mood of the story requires.

With “No Go,” the unusual premise and strong, quirky prose work together to deliver emotional satisfaction as well. In it, Harrison is attempting to write an email to his soon-to-be-ex-wife about their son, and editing software his lawyer recommended interferes. The story acts as an artifact of this interaction, showing Harrison’s attempts at communication riddled with the software’s editing suggestions. Much of the story involves onscreen email exchanges between Harrison and tech support, with Harrison begging for the software to be removed.

Harrison’s fight against the machine embodies a recurring theme in Richardson’s collection – the modern day depersonalization of human interactions, especially in the workplace. The ever-fragmenting structure drives home this theme and pulls the reader deeper into Harrison’s emotional experience, helping us understand that his real frustration and anger stem from his loss of contact with his son. Especially in “No Go,” Richardson’s innovations with premise, structure, and language work in tandem to deliver broader themes and poignancy along with novelty.

Richardson takes a lot of risks in this collection, and there are hazards to risk taking. Not every innovative premise or structure delivers deeper meaning. In “The Lips the Teeth and the Tip of the Tongue,” for example, the story’s section headings are descriptions of imagined auction items. As a structural element, these add flair to the page, but they don’t add meaning or depth. Likewise, in “Our Acts Together,” a grandson tries to help his grandmother prepare for law school by ordering and re-ordering descriptions of legal cases on scraps of paper pinned to the walls. The verisimilitude of the descriptions of these cases gives an unorthodox look to the text but doesn’t deepen our understanding of the story. Throughout the collection, Richardson’s premises and strong writing make for compelling reading, but they don’t always work together to achieve greater ends.

Sometimes the clever wording in Richardson’s writing disappoints. After the homeless narrator’s second rape in “Call Me Silk,” for example, she reports, “But this time I loved it” (15). Perhaps this reaction is meant to reveal the extreme dislocation of the character’s emotional state, but it also feeds into rape mythology, turning something meant to seem quippy and odd into something that darkly mirrors rape culture instead, introducing an intention the author doesn’t seem aware of.

Richardson achieves unique work unfettered by tradition. Despite occasional misfires, on the whole, her writing is snappy and fresh, and her imagination zings onto the page in unexpected scenarios and brand-new modes. The original and the absurd are on virtual parade throughout It Had Been Planned and There Were Guides. Expect to be surprised.

Jody Hobbs Hesler lives and writes in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Her fiction, feature articles, essays, and book reviews appear or are forthcoming in Gargoyle, The Georgia Review, Sequestrum, [PANK], Streetlight, Valparaiso Fiction Review, A Short Ride: Remembering Barry Hannah (VOX Press), Charlottesville Family Magazine, and several regional prize anthologies and other publications. You can learn more about her writing at jodyhobbshesler.com.

Jody Hobbs Hesler lives and writes in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Her fiction, feature articles, essays, and book reviews appear or are forthcoming in Gargoyle, The Georgia Review, Sequestrum, [PANK], Streetlight, Valparaiso Fiction Review, A Short Ride: Remembering Barry Hannah (VOX Press), Charlottesville Family Magazine, and several regional prize anthologies and other publications. You can learn more about her writing at jodyhobbshesler.com.