Aaron Max Jensen

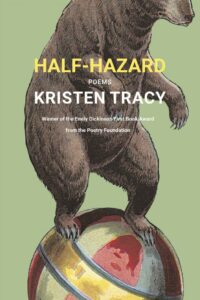

Kristen Tracy’s Half-Hazard is a book centered in the act of observation, a series of examinations of the world of her upbringing that are equal parts hopeful and regretful, yet all dazzling in their stark rendering of the tiny dramas and realizations of the everyday. Full of pigs, mice, and cows, big realizations and subtle heartbreaks, this thrilling debut collection uses the playfulness rooted in Tracy’s background as an author for young readers to engage its target adult audience in a rhetorical contemplation of innocence and nostalgia.

Kristen Tracy’s Half-Hazard is a book centered in the act of observation, a series of examinations of the world of her upbringing that are equal parts hopeful and regretful, yet all dazzling in their stark rendering of the tiny dramas and realizations of the everyday. Full of pigs, mice, and cows, big realizations and subtle heartbreaks, this thrilling debut collection uses the playfulness rooted in Tracy’s background as an author for young readers to engage its target adult audience in a rhetorical contemplation of innocence and nostalgia.

In “Undressed,” a poem from the first section, her tortured speaker recalls “A doctor on the radio / said that a woman should never split herself / into halves, division has consequences.” In the moment of the poem, this refers to a woman struggling with a conflict of identity: the “woman in her” who’s elated to be engaged and enamored with her diamond ring, versus the “little beast,” the part of her that “wants to chew the ring up / and die.”—just one example of an attention to contradiction and duality that permeates the forty-four poems composing this collection. Considering this winner of the Poetry Foundation’s Emily Dickinson First Book Award as the sum of its parts, Tracy’s thorough examination of the divisions with which one arranges a life—the internal and external, personal and ideological—presents nothing short of brilliance as its consequence.

Tracy explores the world of these poems with refreshing clarity, bringing a childlike curiosity and whimsicality to balance her adult perspective without dipping into the childish. This is achieved through the interplay of sound, lyricism, and imagery, delivered in tight narrative packages that often leave one breathless. In “What Kind of Animal,” Tracy uses the death of a pet rabbit to contrast the innocence of a child, who believes a wild animal is responsible for the carnage, with the adult understanding that her father accidentally ran over the rabbit with a lawnmower.

dog, tomcat, it wasn’t clear what found her.

Behind the raspberry bushes, days away

From having her first litter, my pet bled

like a machine. Fully dismantled.

Prey versus predator. I couldn’t stand the story.

What kind of animal has that kind of heart?

This sort of dramatic irony is present in a number of pieces, extending the halving motif into the reader’s conception of memory.

Memories here are portrayed as inherently split between the less experienced perspective of the past and the, often grim, adult understanding of the present. This is abundantly clear in Tracy’s occasional forays into the explicitly political. “Stamps” reveals the disillusionment felt when the political affiliation of the speaker’s upbringing is challenged when faced with a mature understanding of what those politics represent.

The poem begins with the powerful lines, “Back when I was nearly blameless and could visit the zoo / and admire the tigers not for what they actually were, / but as monstrous man-eaters that deserved to be caught.” The poet is careful to emphasize the speaker’s immaturity and naiveté before dropping the bomb of context in the eighth line: “I was a Republican. And I went to work / in Washington, DC, and met all the suited villains / I’d been warned about. Still reading about Goldwater’s / conscience. Thrilled by the idea of bombs.” The phraseology used communicates from the start that the speaker has evolved. She was a Republican back then, and yet the question is not what she believes now, but rather how that evolution was precipitated. On an errand to purchase a thousand dollars in postage stamps for fundraising letters, she is chased down by one of her co-workers.

He told me what my boss had forgotten to say. We can’t

use stamps with women or black people on them. The world

toppled me that day in a business park—so young

and dumb—I left in an instant to become who I really am.

The authority the poet establishes in “Stamps” gives added power to the almost accusatory “What We Did before Our Apocalypse,” wherein Tracy submerges the reader in a list of the newsfeed minutiae of everyday life. “We took the batteries out of the smoke detectors so all the toys / would work. We jiggled the toilet handle to try to fix the problem. / We let people who were acting like assholes merge into / the carpool lane. Orgied out, we debated canceling HBO.” Despite the ordinariness of the images and actions described, there is an unmistakable sense of foreboding woven into the subtext of all these things we did before. There is a shortening fuse, a heightening tension, before Tracy detonates another of her context bombs with the nonchalance of a well-timed punch line: “we all held hands and prayed. We watched an old man insult / nearly everybody and then let him fondle the nukes.”

Brimming with clever moments of humor, pensive moments of reflection and nostalgia, Half-Hazard is as technically impressive as it is rich and imaginative. Kristen Tracy captures the American fascination with the drama of everyday lives that are anything but mundane, cutting to the core of our cultural identity to reveal the joyful, beating heart of a nation perpetually halved by hope and regret.

—

Aaron Max Jensen has an MFA in Fiction Writing with a minor in Poetry from Converse College, and earned his BA in Creative Writing & English from Southern New Hampshire University. His fiction and poetry have appeared in The Penmen Review, and the Pick Your Poison anthology from Owl Hollow Press. He resides in Denver, Colorado with his children.

Aaron Max Jensen has an MFA in Fiction Writing with a minor in Poetry from Converse College, and earned his BA in Creative Writing & English from Southern New Hampshire University. His fiction and poetry have appeared in The Penmen Review, and the Pick Your Poison anthology from Owl Hollow Press. He resides in Denver, Colorado with his children.