Rachel Morgan

In beginning craft classes I’ve said on more than one occasion, “Show. Don’t tell.” When these three syllables first crossed my lips I appreciated their direct and dependable nature. However, upon hearing this advice students reacted in one of two ways: sincere scribbling in notebooks or skeptical brows asking for an example. I obliged and created instantaneous horrible analogies, “Well, ‘Spring is here and bursting with color’ is telling, but ‘the guilt of drunk blossoms bend branches’ is showing.” The more students asked for examples and clarification the more I realized “Show. Don’t tell” is not a panacea for poorly conceived writing or teaching. In fact, saying, “Show, Don’t tell” is telling.

In my own practice as a young poet my teachers urged us away from the dramatic, literal, and hackneyed by pushing surrealism or form, anything to put language in the driver’s seat and ideas in the passenger’s seat. Urging young poets to embrace a metaphor or language, about which meaning or intention is unclear, is one of the most challenging tasks I face as a beginning craft teacher, and probably in my own writing.

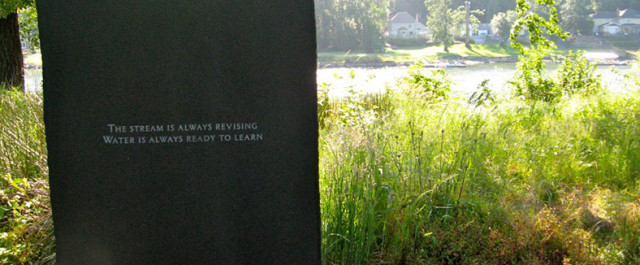

At the beginning of this Spring semester, I happened to be reading Harreyette Mullen’s Urban Tumbleweed, against one of the coldest winters on record. Mullen’s book is a collection of tanka largely set in Los Angeles, and in thirty-one syllables nature that is both natural and man-made, urban sprawl, news, and neighborhoods swirl into a microcosm that reveals a larger ecology and introspection. In her preface, “On Starting a Tanka Diary,” Mullen writes that keeping this diary was a “reminder that head and body are connected,” so she takes her students on tanka walks. Much like haiku, tanka have the ability to say one thing and mean two or three or more things in a small space, which is similar to how metaphors work.

As I took a break in reading I couldn’t help but notice the harsh Midwestern wind curling around the house as another spit of snow gathered. The next week my students and I were taking a tanka walk in the greenhouses on campus. Outside snow was piled on planting benches, condensation was freezing on the windows, but inside daffodils erupted, bromeliads clung to bark, and a few tropical birds called from unseen perches.

William Carlos Williams defined poetry as, “a small (or large) machine made of words.” I asked my students to look at the opposing worlds outside and in, the obvious and invisible work of man to create and sustain a green house in the upper-Midwest. I noticed one student taking notes about the irrigation pipes, another writing down Latinate genius and species, a student brushing droplets off her notebook. I asked them to make machines while thinking of two worlds. Here is what they built:

Take a nap when I touch you, Mimosa pudica.

Look up! Look up! Shirk first from my sight.

I’m a liar, a fraud. If not embraced, who am I?

-Elana Williams

Flesh lacks chemical

substance and pulse, slips of sheets

glued, paper mache,

veins, blue ink of his life quiet

like the lips I help stitch shut.

– Connor Ferguson

Rachel Morgan is the Assistant Poetry Editor for the North American Review and teaches creative writing at the University of Northern Iowa. She co-edited Fire Under the Moon: An Anthology of Contemporary Slovene Poetry. A letterpress chapbook of her poetry, Things We Lost in the Fire, was published by Flag Pond Press. Recently her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Fence, Denver Quarterly, DIAGRAM, Volt, Hunger Mountain, and South85 Journal.

Scott Laughlin teaches English at San Francisco University High School and is co-founder and Associate Director of

Scott Laughlin teaches English at San Francisco University High School and is co-founder and Associate Director of  Shea Faulkner holds a Master’s of Education from Southern Wesleyan University and is pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing from Converse College. Shea’s primary literary interests include the Southern family as portrayed by Southern writers. She currently works as an adjunct English and Reading instructor at Spartanburg Community college and is an independent quality consultant. She and her husband, Campbell, reside in Upstate, SC, with their two children, Ian and Caroline.

Shea Faulkner holds a Master’s of Education from Southern Wesleyan University and is pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing from Converse College. Shea’s primary literary interests include the Southern family as portrayed by Southern writers. She currently works as an adjunct English and Reading instructor at Spartanburg Community college and is an independent quality consultant. She and her husband, Campbell, reside in Upstate, SC, with their two children, Ian and Caroline.

Scott T. Starbuck

Scott T. Starbuck