Russell Jackson

Desks hold a lot of importance and significance for some people. For some they are merely a workspace; a table with four legs they begrudgingly sit at each day. Some desks go down in history like Harry S. Truman’s desk in the Oval office which held the now iconic line: “The Buck Stops Here.” For others desks represent an almost sacred space. This is true for a lot of writers I know. I’ve also read articles and books by writers on the craft of writing and they’ve suggested creating a special space with a desk where you will be pulled to each day to write.

The poet Carl Sandburg had a desk in his main office on the first floor of his Connemara estate located in Flat Rock, North Carolina. The desk held major significance for him because the desk had been made especially for him from the wood flooring from Abraham Lincoln’s office. Sandburg was not only a huge fan but he also won his first Pulitzer Prize for his biography on Abraham Lincoln. Even though his office desk held much meaning for Sandburg he often wrote upstairs on an old orange crate which held one of his trusty typewriters, but he and the orange crate migrated throughout the house as well. Sandburg also often wrote outside with the trusty old pen and paper.

Carl Sandburg is a hero of mine. His home which is now a national state park is open to the public in my hometown so as a kid the usual field trip was a visit to Connemara Farms complete with a tour of the home in which Sandburg spent his last twenty or so years. I was in second grade when my first field trip to Connemara took place and the minute I saw the typewriter atop the old orange crate I set about becoming a writer. It seemed like such an amazing thing to me to be able to seclude myself in a cozy little nook somewhere and write. So I grabbed an old apple crate and my dad’s Smith and Corona and set about creating my own little Sandburg space and becoming a successful writer. But even as a kid that crate kept moving or being discarded for another surface. Perhaps some of Sandburg’s hobo ways rubbed off on me.

I too have a special desk which was inherited from my great grandmother Sallie Hunter Jones, who taught school and retired as principal. The desk I inherited is her desk that she used as teacher and principal. Personally I’ve found it difficult to stick to a special place and desk especially created for my writing. I used to worry that because I didn’t do a lot of what these writers of writing books do that it meant I was not a serious writer. A kind fellow writer reminded me that the suggestions in these books are just that: suggestions. I find I have no control over where I am at when the urge to write hits and I have learned the hard way that I don’t put off those little moments of inspiration until I get back to my “writer’s space.”

When I moved back to my hometown this past summer me and my dad begin repairing and renovating my grandmother’s little place for my new home. As I’m nearing the end stage of that renovation process and begin setting up house I look at my little desk and wonder that if I did find some special nook or cranny would it somehow jumpstart my motivation to write each day. Now that I’m older and more settled and in a graduate program- maybe the desk and its space will perhaps work for me now. My suspicion is that for me that has not changed. Perhaps the desk and its locale represent a safe harbor and maybe it’s enough to know it is there waiting on me should the orange/apple crate and hobo writing life prove to be fruitless.

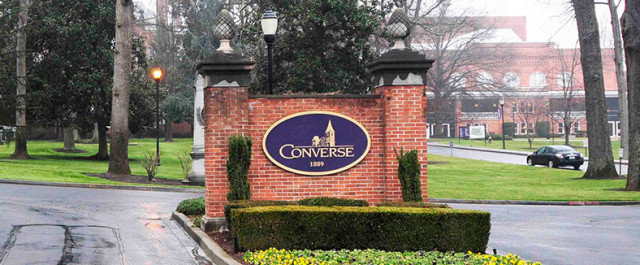

Russell Jackson is a graduate of Evergreen State College and current graduate student at Converse College in the MFA Creative Writing Program. He recently discovered that Back to the Future was just a fantasy created by Hollywood, so he and his poetry spend a lot of time circling the drain of childhood nostalgia and pop culture.

Russell Jackson is a graduate of Evergreen State College and current graduate student at Converse College in the MFA Creative Writing Program. He recently discovered that Back to the Future was just a fantasy created by Hollywood, so he and his poetry spend a lot of time circling the drain of childhood nostalgia and pop culture.