Louie Crew Clay

Isolated in rural South Carolina in 1971, I fumbled around the cheese table as we celebrated poet Patricia Henley’s new chapbook of poems. She came over. We had not met; we were both new to Claflin College in Orangeburg, SC, which had just hired her husband and me to teach English. Most of the guests were old-timers on the faculty.

“I’m Louie, a poet too,” I sloshed tentatively, through a mouthful of chianti and cheddar.

“Good,” Pat said. “What have you published?”

“Oh, only two poems back in graduate school. Mainly I write just for myself,” I spoke more soberly.

“Louie, would you call yourself a chef if you cooked only for yourself?”

Praise all Goddesses for psychic Draino®.

When smart had turned to smart, I visited her. She lived in the large rickety old house at the head of the lot. I lived in a small servants’ house in the pecan orchard that was her backyard. Her husband and I were renters.

Pat showed me how she posted manuscripts; introduced me to a new bible, the International Directory of Little Magazines and Small Press Books, then in its 4th or 5th edition; taught me about crisp stationery, SSAEs…; and braced me to expect rejection as routine.

Pat and I soon moved to distant parts. I have not seen her in 45 years, but we reconnected through Facebook two years ago. She is still writing and publishing, now more fiction than poetry. I love her work, especially her novel In the River Sweet. I am enormously grateful to her for the prompt to get serious, to clean out the dresser drawer where I used to stash literary dabbles, and more important, write, write, write, write….

On Valentine’s Day, 2017, my computer reported: “Editors have published 2,691 of Louie Clay’s manuscripts. The last 4,798 editors took an average of 38 days to decide. The last 1,883 editors who have accepted his work have averaged of 15.5 months from acceptance to publication.” Pat, see what you prompted!

I taught the computer to track circulations so that I had more time to ‘get a life.’ In the 1980’s I wrote a computer program. My Agent, and shared it with hundreds of others to free up time for them, and from 1996-2016 I maintained a website to list “Poetry Publishers Willing to Receive Submissions Electronically.” Only a few publishers were willing to be listed at the beginning, but 20 years later, over 1,000 seized the opportunity. Writers and publishers alike continue to thank me for connecting them, but the real pleasure was mine. We can strengthen the vitality of writers’ community by simple acts of hospitality.

Shoals of Change

When Bell invented the telephone,

someone asked him what he might do with it.

“Call ahead to say ‘Your telegram is on the way.'”

Twain used one of the earliest “computers”

but hid the fact lest some think

the typewriter did his thinking for him.

In 1983, I sold great-grandmother’s

calendar clock, with the snuff box

always on it to buy my first computer

a portable, 24 pounds, encased

like a sewing machine.

I sneaked it into China,

Customs baulked:

“It’s a spy machine!”

“No, it’s a Hollywood typewriter.”

B.C. (before the Computer),

whenever someone showed up

at the door asking for me,

my husband would say, “Just a minute.

He’s working in the study.”

After the computer, he said, “Just a minute.

He’s in the study playing with the computer.”

What magic to transform work into play.

I have plenty of old books

in which to press flowers,

and I love them,

as I love Mother’s Victorian dining room set.

After my first computer, I kept an IBM Selectrix

for several years only to address envelopes.

When I chaired Rutgers University senate,

a dean complained that he had not received

a copy of the document we were discussing.

“But we sent it to you by email.”

“I don’t read email,” he huffed.

“Rutgers has spent thousands of dollars

so that we can communicate electronically.

If you prefer to ride to work on your horse,

that is entirely your right,

but do not expect Rutgers to provide

either a groom or a hitching post.

You might ask your secretary to read your email.”

He did.

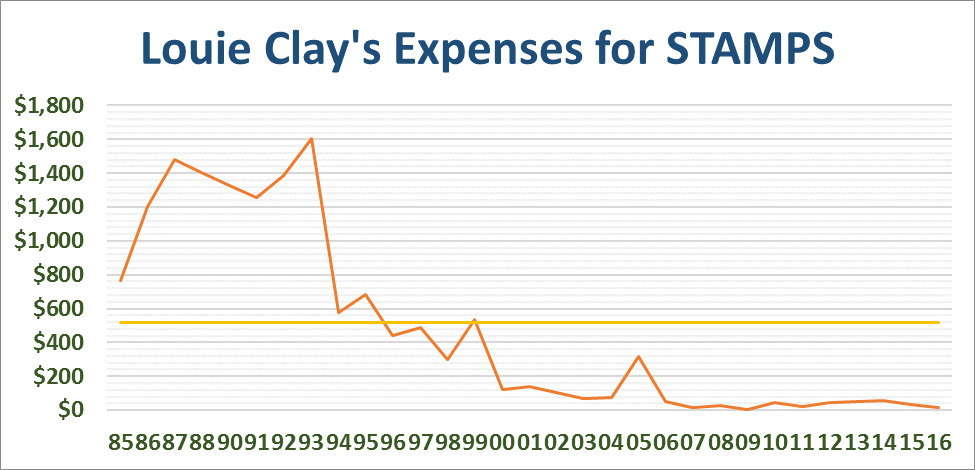

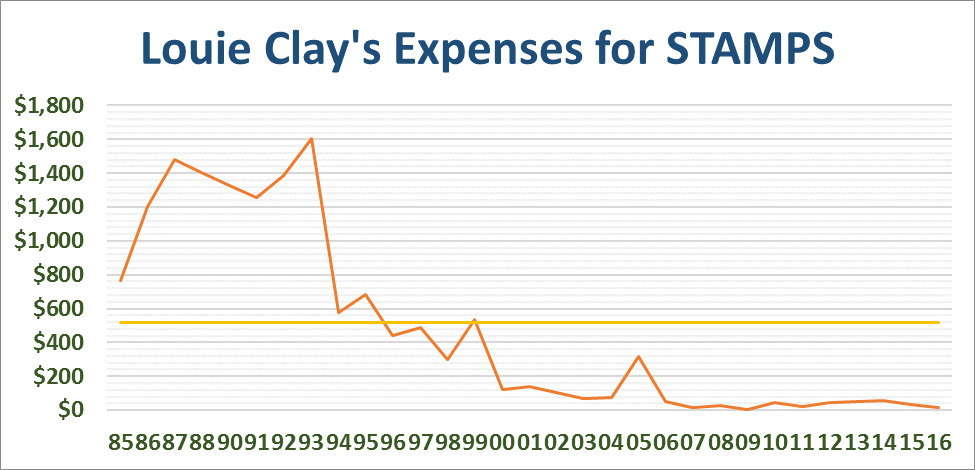

Writers and publishers did not invent these changes, and I had no illusions that I invented them either. In addition to the time computers save, and the many ways computers make it easier to create, revise, and share manuscripts, computers save money.

Economics nudged reluctant writers and publishers to move from typewriter to computer.

I sometimes feel guilty for knowing more about the business part of writing than is seemly. I work hard at writing, and I work hard at placing my manuscripts to reach audiences. These skills are separate and distinct, and I choose to keep them that way. When I am in the throes of writing, I don’t go near my data regarding circulations and publications. There is fallow time aplenty for that important work. When I am in fallow period, I am more efficient at organizing the busy work.

Nor am I daunted by rejection. Disappointed at times, of course, but never daunted. Before I ever send out a manuscript, I identify one or more additional publishers to approach if the current one rejects it. Usually I can recirculate the material within a day, often with revisions I have already made since the last submission.

I would not dare seek validation as a writer by the decision any editor or publisher makes regarding one of my manuscripts. Nor would any editor with good sense presume to speak for all others.

I know many who write better than I do but are daunted by rejection. Some stop circulating a manuscript for months before trying again. Any day that I sit on a rejected manuscript, is another day that the manuscript is not sitting in the next editor’s queue.

Through the internet writers have excellent, up-to-date ways to inform themselves about what is expected, yet editors report that many who submit have obviously not read the publication and have no idea about its stated priorities.

The best-known publications are likely the ones most overloaded with submissions. Given their status, some of those prefer to solicit manuscripts from established writers rather than wait for them to arrive over the transom. Submit to these anyway? Why not, so long as we don’t measure our worth by their decision. As Eleanor Roosevelt famously said, “No one can make you feel inferior without your consent.”

A classmate in graduate school had the opposite problem. Very early in his writing life, The New Yorker published one of his poems. To hold that reputation, from then on he submitted only to The New Yorker and a handful of others he thought prestigious enough. Quite soon the only audience he commanded were others at his favorite bars. He died a distraught alcoholic in an alley of The City That Care Forgot.

I write because I write, just as I eat and sleep because I eat and sleep. I write for any audience I can get, and when I can’t get someone, I’ve been known to get on a bus and natter to no one in particular. People listen, and some respond. A couple of times fellow travelers put up such an echo that others mutter as they leave, “Bunch of loonies taking over the world.” These too speak to nobody in particular.

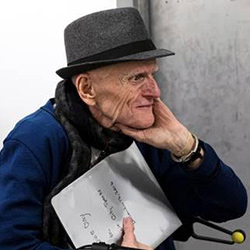

Louie Crew Clay, 80, is Professor Emeritus at Rutgers University. He and Ernest Clay, his husband for 43 years, live in East Orange, NJ.

Clay has been a fellow at the Ragdale Foundation (1988) and at the Helene Wurlitzer Foundation (1963). He directed Rutgers University’s New Jersey High School Poetry Contest from 1990-1999.

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louie_Crew#Queer_Poet_and_Writer. The University of Michigan collects Clay’s papers.

Author Photo Credit: Louie Crew Clay. ©2016 by Cynthia L. Black. Used with her permission.

Jessica (Tyner) Mehta (Jey Tehya) is a Cherokee poet and novelist. She’s the author of four collections of poetry including Secret-Telling Bones, Orygun, What Makes an Always, and The Last Exotic Petting Zoo as well as the novel The Wrong Kind of Indian. Jessica is the owner of a multi-award winning writing services business, MehtaFor, and is the founder of the Get it Ohm! karmic yoga movement. Visit Jessica’s author site at www.jessicatynermehta.com.

Jessica (Tyner) Mehta (Jey Tehya) is a Cherokee poet and novelist. She’s the author of four collections of poetry including Secret-Telling Bones, Orygun, What Makes an Always, and The Last Exotic Petting Zoo as well as the novel The Wrong Kind of Indian. Jessica is the owner of a multi-award winning writing services business, MehtaFor, and is the founder of the Get it Ohm! karmic yoga movement. Visit Jessica’s author site at www.jessicatynermehta.com.

Mel Sherrer is a performance poet and teacher living in San Marcos, Texas. She is the Managing Poetry Editor for South 85 Journal.

Mel Sherrer is a performance poet and teacher living in San Marcos, Texas. She is the Managing Poetry Editor for South 85 Journal.

Kelly Abbott is a veteran entrepreneur in publishing. He lives in San Diego. He is the grandson of the founder of the Roswell UFO Museum.

Kelly Abbott is a veteran entrepreneur in publishing. He lives in San Diego. He is the grandson of the founder of the Roswell UFO Museum. Katie Sherman is a freelance journalist in Charlotte, NC. She is currently pursing an MFA degree at Converse College. She has an affinity for Southern Gothic literature, cider beer, Chicago, and morning snuggles with her girls — Ella and Addie.

Katie Sherman is a freelance journalist in Charlotte, NC. She is currently pursing an MFA degree at Converse College. She has an affinity for Southern Gothic literature, cider beer, Chicago, and morning snuggles with her girls — Ella and Addie.