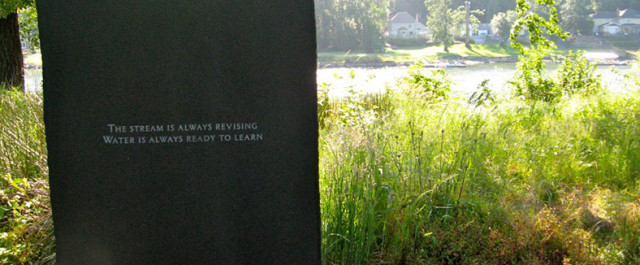

Photo credit: Becca J.R. Lachman

Scott T. Starbuck

The 2008, and following years, financial, social, and environmental meltdowns changed how I write. Way before that, I was a skeptic of mainstream news, but after seeing millions lose homes, savings, and jobs while the planet was BP-ed, fracked, and “Fuk-ed” (Fukushima-ed), I ignored ubiquitous sensationally irrelevant news. In other words, David W. Orr’s statement in Children And Nature that “young people on average can recognize over 1000 corporate logos but only a handful of plants and animals native to their places” matters more to the future of humans than much of what is said in the NFL, NBA, or CNN. Instead of using only traditional media, I get my poetic inspiration, as Noble Prize Winning Polish poet Czeslaw Miłosz, from striving to see reality. When I gave up television at age 15, my ability to hear and recall poem-worthy personal and social events dramatically increased.Having read James Hansen’s May 9, 2012, New York Times OP-ED “Game Over for the Climate” and having watched Bill McKibben’s February 10, 2014, video interview at Moyers & Company, I’m writing a poem today in strong opposition to the Keystone XL pipeline.

Chen-Ning Yang, who won the Noble Prize in Physics in 1957, said in a 1988 Bill Moyers World of Ideas interview “We have something like 10 billion neurons, maybe 100 billion. [ . . . .] And each neuron has something like 10,000 to 100,000 synapses.” However, the 2008 agenda-driven businessmen and their political puppets want you to mind-drive your thought car down one neuron road: theirs. Don’t. By comparison, with only 32 chess pieces, writer Marshall Brain, in his electronics.howstuffworks.com article “How Chess Computers Work,” notes “If you were to fully develop the entire tree for all possible chess moves, the total number of board positions is about [10 to the 120th power], give or take a few.” That means even though many of us have been boxed for the 12 best years of our lives, or much longer, we could think of neurons as chess pieces capable of many different moves, and then divergent and original thoughts will become possible.

Jacob Boehme and Robert Bly show the kinds of “divergent and original thoughts” to which I am referring. Jacob Boehme was quoted in Robert Bly’s Vietnam War protest poems The Light Around the Body: “When we think of it with this knowledge, we see that we have been locked up, and led blindfold, and it is the wise of this world who have shut and locked us up in their art and their rationality, so that we have had to see with their eyes.” Bly’s book won the 1968 National Book Award for Poetry, and in his acceptance speech he said, “Every time I have glanced at a bookcase in the last few weeks, the books on killing of the Indians leap out into my hand. [ . . . . ] As Americans, we have always wanted the life of feeling without the life of suffering. We long for pure light, constant victory. We have always wanted to avoid suffering, and therefore we are unable to live in the present. [ . . . .] Since we are murdering a culture in Vietnam at least as fine as our own, do we have the right to congratulate ourselves on our cultural magnificence? Isn’t that out of place? [ . . . ] I thank you for the award, and for the $1,000 check, which I am giving to the peace movement, specifically to the organizations for draft resistance. That is an appropriate use of an award for a book of poems mourning the war.”

One way to escape the “ubiquitous sensationally irrelevant” Machine is to walk beaches, rivers, deserts, or mountains, and listen to their voices, and to the spirits of creatures that inhabit them. Try it, and ideas will naturally surface like coastal cutthroat trout to flies.

In addition to the idea of poetic striving for reality, aforementioned Milosz advanced the concept of provinces in one’s life, and I agree that one’s stage in life can be a strong influence on poetic art. Whitman, “considered one of America’s most important poets” by the Academy of American Poets, wrote about what it felt like to grow old in his classic Leaves of Grass. I recently became a godfather of my niece Sky Starbuck which led me to compile a godfather box of important items like The Power of Myth videos by Joseph Campbell, influential poems like William Stafford’s A Glass Face in the Rain, and necessary films like Winter’s Bone. Even more importantly, I am cultivating a godfatherly attitude, which means advocating a future of sustainability and wholeness instead of the runaway train we are on to ecocide.

My poetic goal, therefore, is to produce essential work for humans who have, or will have, capacity to care, time to reflect, and willingness to act in meaningful literary, place-or-community based, and/or activist ways.

Scott T. Starbuck is a former charter captain and commercial fisherman turned poet and creative writing professor. His latest poetry collection, The Other History or unreported and underreported issues, scenes, and events of the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries, was published by FutureCycle Press. He will read from it in San Diego City College’s Spring Literary Series on March 12, 2:30 – 3:55 p.m. in V-101 , and offer the chance for attendees to write eco-poems and share them as time allows. Starbuck feels destruction of Earth’s ecosystems is closely related to spiritual illness, and widespread urban destruction of human consciousness.

Scott T. Starbuck is a former charter captain and commercial fisherman turned poet and creative writing professor. His latest poetry collection, The Other History or unreported and underreported issues, scenes, and events of the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries, was published by FutureCycle Press. He will read from it in San Diego City College’s Spring Literary Series on March 12, 2:30 – 3:55 p.m. in V-101 , and offer the chance for attendees to write eco-poems and share them as time allows. Starbuck feels destruction of Earth’s ecosystems is closely related to spiritual illness, and widespread urban destruction of human consciousness.

One thought on “The Godfather Box”

Comments are closed.