Terry Lucas

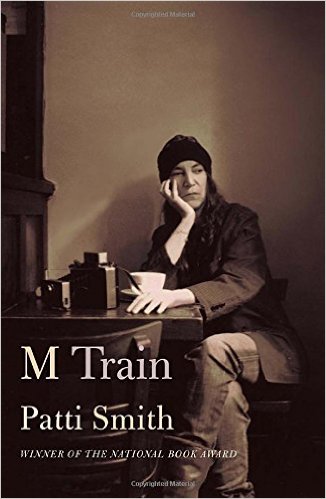

Asked to locate M Train with reference to genre, students of literature would, overwhelmingly, place Patti Smith’s latest romp through her sometime outrageous, but always entertaining pilgrimages—both geographical and mental—if not squarely in the middle of memoir, at least inside its borders. Although her stories chronicle trips to destinations as divergent as New York, French Guiana, Glasgow, and Mexico, the work is written with the attention and care that a poet pays to language, often bringing words themselves to the forefront, and turning them loose like the dogs of Alicia Ostriker’s poem, “The Dogs at Live Oak Beach in Santa Cruz,” to cross the moving surf between prose and poetry, jumping from the sand of narrative into the foaming waters of lyricism, and then “…bound[ing] back to their owners / Shining wet, with passionate speed / For nothing, / For absolutely nothing but joy.” Thus, many readers will experience M Train, if not as prose poetry, at least as poetic prose.

Asked to locate M Train with reference to genre, students of literature would, overwhelmingly, place Patti Smith’s latest romp through her sometime outrageous, but always entertaining pilgrimages—both geographical and mental—if not squarely in the middle of memoir, at least inside its borders. Although her stories chronicle trips to destinations as divergent as New York, French Guiana, Glasgow, and Mexico, the work is written with the attention and care that a poet pays to language, often bringing words themselves to the forefront, and turning them loose like the dogs of Alicia Ostriker’s poem, “The Dogs at Live Oak Beach in Santa Cruz,” to cross the moving surf between prose and poetry, jumping from the sand of narrative into the foaming waters of lyricism, and then “…bound[ing] back to their owners / Shining wet, with passionate speed / For nothing, / For absolutely nothing but joy.” Thus, many readers will experience M Train, if not as prose poetry, at least as poetic prose.

Most of the time M Train rides along narrative’s linear tracks. But from the beginning, as well as throughout its journey, Smith’s train of thought begins on a siding. And, throughout the book, it only takes the flick of a switch to get back onto a parallel route that winds through space and time with little regard for what is sequential, or even possible. As with her musical lyrics, the main criterion is whether her language strikes an artistic chord that subverts the audience’s expectations. Like a poet, Smith begins her work with an image that turns into a book-long conceit—a dream about “nothing”— in a way that might remind poetry readers of Larry Levis’s “Nothing” in “At the Grave of My Guardian Angel: St. Louis Cemetery, New Orleans,” a nothing that is more a presence than an absence:

Riding beside me, your seat belt around your invisible waist. Sweet

Nothing.

Sweet, sweet Nothing.

“It’s not so easy writing about nothing,” Smith begins with an enigmatic pronouncement from a cowpoke in her dream, before continuing:

…Vaguely handsome, intensely laconic, he was bal-

ancing on a folding chair, leaning backwards, his Stetson

brushing the edge of the dun-colored exterior of a lone café. I

say lone, as there appeared to be nothing else around except an

antiquated gas pump and a rusting trough ornamented with a

necklace of horseflies slung above the last dregs of its stagnant

water. There was no one around, either, but he didn’t seem to

mind; he just pulled the brim of his hat over his eyes and kept

on talking. It was the same kind of Silverbelly Open Road

model that Lyndon Johnson used to wear.

It would be more accurate to say that Smith writes from nothing, seemingly beginning the book, indeed, each chapter, with no thought in mind as to where it might end, and yet still managing to fill pages with memorable images and characters that prove to be worthy traveling companions. Presented as a series of riffs on life and loss that we learn quite late in the book have been assembled from scribbled-on scraps of paper, Smith’s text is more palpable than much writing that is carefully planned from beginning to end. In addition, Smith’s superb Polaroid photographs, appropriately placed throughout, add to the collage-like assemblage of genres, and create a more complete and enduring work of art.

However, Smith’s characters also have an ephemeral quality to them. One of the reasons—other than the fact that she writes a lot about people who have passed from her life—is that they are not limited to human subjects. Cafés with names like Ino and Dante transform into best friends from New York, and a house at Rockaway Beach into a love affair. These places, and many other cafés and bars around the world, serve as witnesses to Smith’s life and work, sharing a palliative coffee when she is down, and a celebratory shot or two when she is up—cafés that might bequeath a favorite chair when they die, or not notify her when they move—she returning years later to their last known address to find a vacant lot. Here is the account of her falling in love at first sight with a ramshackle beach house in the throes of death—a house that changed her life when she rescued it from destruction, a process by which she rescued herself, as well:

I stood in front of the fence on tiptoe and peered through the broken slat. All kinds of indistinct memories collided. Vacant lots skinned knees train yards mystical hobos forbidden yet wondrous dwellings of mythical junkyard angels. I had lately been seduced by a piece of abandoned property described in the pages of a book, but this was real. The For Sale by Owner sign seemed to radiate like the electric sign Steppenwolf comes across while on a solitary night walk: Magic Theater. Entrance Not for Everybody. For Madmen Only! Somehow the signs seemed equivalent. I scribbled the seller’s phone number on a scrap of paper and walked across the road to Zak’s café and got a large black coffee. I sat on a bench on the boardwalk for a long time, looking out at the sea.

In spite of the fact that her friends and legal advisors told her she was crazy to give this property a second thought—that it was practically worthless now; that it would cost her a fortune to renovate; and that she could probably never sell it and recover her investment—she proceeded to court it, not even having seen its interior, saying that those were the precise reasons she knew they were right for one another. Here she is asking for her beloved’s hand, even before the two have ever been alone:

A few days later the seller’s daughter-in-law, a good-natured young woman with two small boys, met me in front of the old blockade fence. We could not enter through the gate, as the owner padlocked it as a safety precaution. Klaus had given me all the information I needed. Because of its condition and some tax liens it was not a bank-friendly property, so the buyer would be obliged to produce cash. Other prospective buyers, seeking a bargain, had grossly underbid. We discussed a fair amount. I told her I would need three months to raise the money, and after some discussion with the owner, all agreed.

—I’m working all summer. When I come back in September I will have the sum I need. I suppose we will have to trust one another, I said.

We shook hands. She removed the For Sale by Owner sign and waved good-bye. Although I was unable to see inside the house I had no doubt that I had made the right decision. Whatever I found to be good I would preserve, and transform what was not.

—I already love you, I told the house.

Beginning with the story of traveling with her husband, Fred, to the prison at Saint-Laurent in French Guiana to collect stones for the grave of Jean Genet, the French novelist, activist, and petty thief that served time in lesser-known jails and prisons, and whose aspiration to make it to Saint-Laurent was never reached, to Smith’s final story of Fred’s death, the multiple narrative arcs somehow connect. Smith is convinced that this affinity exists not because of any careful selection of events on her part, but because, like all human activities eventually do, they discovered their own innate connections. After the final chapter was written, Smith recognized that the story didn’t end there—that she had just closed the lid and tied a bow around a package that refused to remain shaped by the nonce form she had chosen for it. So Smith added a postscript that begins with a summary of her book better than anyone else could write:

The arcs had joined, forming a circle. A wagon wheel of words, with spokes wound from strips of sun and desert, a poet’s arrow, trails of the wind-up bird, stepping stones from St. Laurent prison to the grave of Genet, and a redeeming dream of Fred. So many moments relived, scrawled in notebooks and on paper napkins punctuated by quantities of black coffee. There was something so appealing about writing directly to the projected reader, it was hard to let it all go, and like an actor haunted by the wisp of a cast-off character, I found myself unable to completely break from the world of its continuum.

If you are looking for a memoir that conforms to Mary Karr’s success formula of a “split self or inner conflict [that] must manifest on the first page and form the book’s thrust or through line—some journey toward the self’s overhaul by book’s end,” M Train is, likely, not for you. If, on the other hand, you are taken with the art of discovering the connections between language, photographs, and life lived with no particular resolution—full of thousands of details written about and celebrated for themselves, while drinking an ocean of coffee—you will love M Train. For there are an endless number of pages where one may board or disembark. The following passage, one of her many references to her opening dream conceit, although neither at its final stop, nor at the beginning of a new journey, can serve as either:

I went into the back room but the coffeemaker, beans, wooden spoons, and earthenware mugs were all gone. Even the empty mescal bottles were gone. There were no ashtrays and no sign of my philosophic cowpoke. I sensed he had been heading this way and most likely, spotting the spanking-new paint job, just kept on going. I looked around. Nothing to hold me here, either, not even the dried carcass of a dead bee. I figured if I hustled I might spot the clouds of dust left behind where his old Ford flatbed passed. Maybe I could catch up with him and hitch myself a ride. We could travel the desert together, no agent required.

—I love you, I whispered to all, to none.

—Love not lightly, I heard him say.

Who is to say whether in this passage Smith is back in her dream reminiscing about another coffee house closed down, or actually standing in a coffee house speaking metaphorically, using imagery from her dream world, to mourn another kind of loss before moving on. The beauty of Smith’s work is that it doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter in the same way that whether we read it as poetry that allows chance to determine line breaks, or whether as prose that heightens its language with sound work like “me/be,” “hustled/dust left,” and “ride/required,” we reach the same destination in the end: a place where we “whisper” to a universe that contains both every thing and no thing; and, like Smith, we receive whatever answer that we need to hear.

Terry Lucas is the author of two prize-winning poetry chapbooks: If They Have Ears to Hear (winner of the 2012 Copperdome Chapbook Award from Southeast Missouri State University Press), and Altar Call (published in Diesel, the anthology of the 2013 San Gabriel Valley Literary Festival). His two full-length collections are In This Room (CW Books, 2016), and Dharma Rain, just released this October by Saint Julian Press. Terry is a guest lecturer in the Dominican University of California low-residency MFA Program, the Co-Executive Editor of Trio House Press, and a free-lance poetry consultant at www.terrylucas.com.

Terry Lucas is the author of two prize-winning poetry chapbooks: If They Have Ears to Hear (winner of the 2012 Copperdome Chapbook Award from Southeast Missouri State University Press), and Altar Call (published in Diesel, the anthology of the 2013 San Gabriel Valley Literary Festival). His two full-length collections are In This Room (CW Books, 2016), and Dharma Rain, just released this October by Saint Julian Press. Terry is a guest lecturer in the Dominican University of California low-residency MFA Program, the Co-Executive Editor of Trio House Press, and a free-lance poetry consultant at www.terrylucas.com.