Terry Lucas

Some poetry books appear to be a collection of random, stand-alone boxes assembled over time and arranged long after their creation into a presentation that attempts to show each in its best light. Individual poems bump up against one another, share their whorled-grain frames, a few annual rings, a little color, some texture. Others seem more like strings of beads, connected to one another in a calculated way, each occupying its necessarily precise space on the strand, leaving no wiggle room.

Some poetry books appear to be a collection of random, stand-alone boxes assembled over time and arranged long after their creation into a presentation that attempts to show each in its best light. Individual poems bump up against one another, share their whorled-grain frames, a few annual rings, a little color, some texture. Others seem more like strings of beads, connected to one another in a calculated way, each occupying its necessarily precise space on the strand, leaving no wiggle room.

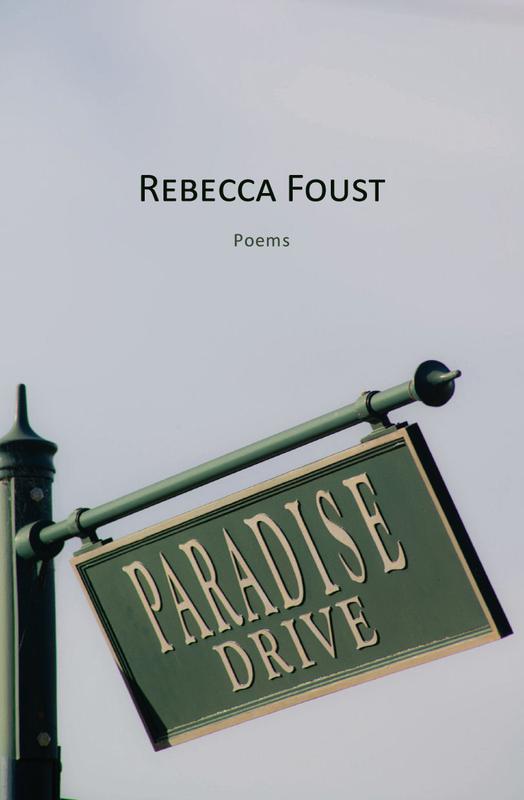

Rebecca Foust’s Paradise Drive has borrowed the best from each arrangement, leaving the downsides to other collections. Though the larger work is an organically connected strand of sonnets that is more than the sum of its individual gems, each poem can be appreciated for its own gorgeous luster, and includes the totality of the larger journey of one and every pilgrim making her way through a “bright ruin” of dreams. “Paradise Drive,” Foust’s title poem, is emblematic of not only the theme of the collection—correctly characterized by Press 53’s Poetry Series Editor Tom Lombardo as one woman’s “pilgrimage from the roots of debt and despair in a small manufacturing town to wealth and despair in one of the most precious pieces of real estate in the United States”—but also of this strategy of every poem standing alone, yet telling not only its story, but the story of the entire collection. Thus, each poem becomes a microcosm of both the greater work’s form and content, and like “each day” of the final line, “bound to the last with dark thread,” the poems hang together typographically, ideationally, and sonically. And although the book is comprised solely of sonnets remaining true to their fourteen-line origins and rife with poetic devices—something rare in today’s trendy, cross-genre literary landscape—they are crafted and voiced in a way that pushes against the boundaries of strict rhyme schemes and stanza lengths, without sacrificing the sonnet’s advantages of narrative compactness and lyrical flexibility.

If there is a flaw in Paradise Drive, it is that the collection is so capacious ideationally, moving with ease from poems of scarcity to poems of opulence, from pilgrim’s quest for internal peace to external acceptance, from dealing with family concerns to standing in awe of nature, that one could write multiple reviews and not cover all the territory mapped. At ninety-five pages of poems and notes, the book is almost twice as long as the standard collection, causing this reviewer to question the need for a total of thirty-one poems, however masterfully crafted, all set at parties where Pilgrim most often locks herself in the bathroom

. . . not for coke

as others supposed, but for something

more covert and rare: a book,

or any bit of anything written. An antidote

to the twitter Out There: the Times

or a Wall Street Journal stowed by the toilet,

the labels on the bottles of balms

ranked at the sink.

In one of the most ambitious and successful series of poems, entitled “The Seven Deadly Sins Overheard at the Party,” Foust addresses the Pauline rubrics of greed, pride, envy, lust, wrath, gluttony, and sloth as persona poems, all in the context of twenty-first century Marin County opulence, evidenced by titles and lines such as “PRIDE, Bickering with Vanity” (“No, I don’t think I’m better than you / because I’m wearing these Birkenstocks / made from recycled rubber

. . .”), and “SLOTH, Just Wanting to Go for a Sail” (“You could say I sonneteer like some sail: / on weekends, in fair weather, ever inside / the curve of a warm, shallow bay . . .”). In “GREED, Exercising Noblesse Oblige” the speaker defends her wealth with the time-honored justification of trickle-down economics:

Yes, our house is the size of the Queen Mary 2,

but that’s okay because we give so much

money away. We made ‘Grizzly Patch’

in last year’s Bear Hugs Campaign, and guess who

got named ‘Redwoods’ in the Spring Garden Tour,

and in 41-point font in the program?

No fools we, giving to the private schools

that (and he worked for it, too) will ensure

Billy’s admission to Harvard. Thus do loaves

and fishes, tossed on the waters, return

as blue whales to be harpooned again.

The price tag on my suit? What absolves that

is my tailor, whose job depends on this tux:

Brioni, bespoke, and better than sex.”

If the contrast between the opulence of Marin County (epitomized by “Paradise Drive”), and the poverty of Altoona, Pennsylvania is one of its themes, then partying is one of the book’s storylines—in both places. Lest one think that only the rich indulge in drug-induced superficiality, with poems like the “Party Etiquette” series (“Remain Upbeat and Polite,” “Elocution,” “Don’t Talk About This,” and “Another Party, Another Bathroom”—“Yes, Pilgrim’s at it again, hiding out / with a book while the bright party sparkles / elsewhere . . .”),—Foust reminds us in “The Truth” about one of the common denominators of human failing:

I’m ready to tell the truth about Dad,

extolled as a death camp liberator.

He was drunk when he tripped on the stair.

What punctured his lung was his own rib

snapped in three places, not the long blade,

oiled, hung over his tools. . . .

. . . . He was false and flawed and still

someone’s god, each 3-a.m. sobbed drunk-dial call.

What a gorgeous metaphorical sense resides in these poems. Not only is each one connected to the previous with the narrative arc of Pilgrim’s quest, but also each poem, like each day, is connected to the first, and to the ultimate poem, “Preparation for Pirouette” from the final section “O Earth Return”:

…It was that last breath

shirring the flesh at her throat, the sign that she

—drawn utterly inwardly taut—was braced

to her clenched core against death. One day, my turn

to make a wreath of my arms, rise up en pointe—

then, whip-pivot-spot—be gone.

Let my throat ache then, be notched. Each flawed dawn.

Paradise Drive, at ninety-five pages, is not merely a three-hour tour—one reading will not satisfy, but only tantalize readers to explore the full range of human emotion and intellect that Foust’s narrator points out along her journey. Leonard Cohen comes to mind: “There is a crack, a crack in everything, / That’s how the light gets in.”

Foust’s smart poems have figured out a way to allow their elixir, mixed from both classical and contemporary vials, to be poured into vessels forged into shapes strong enough to hold the gravitas of the human condition, each one designed with the same time-honored familiar form that best suits story-telling in poems—not exactly cracked, yet scored with marks deep enough to allow their translucence to shine through, without having to shatter the sonnet form or to be completely contained by it. In the process, Paradise Drive emerges as a unique and necessary work of fine art.

Terry Lucas won the 2014 Crab Orchard Review Special Issue Feature Award in Poetry. His most recent chapbook, If They Have Ears to Hear, won the Copperdome Award from Southeast Missouri State University Press, and his full-length collection of poems, In This Room, is forthcoming from CW Books in February of 2016. Terry is Co-Executive Editor of Trio House Press, and a freelance poetry consultant at www.terrylucas.com.

Terry Lucas won the 2014 Crab Orchard Review Special Issue Feature Award in Poetry. His most recent chapbook, If They Have Ears to Hear, won the Copperdome Award from Southeast Missouri State University Press, and his full-length collection of poems, In This Room, is forthcoming from CW Books in February of 2016. Terry is Co-Executive Editor of Trio House Press, and a freelance poetry consultant at www.terrylucas.com.