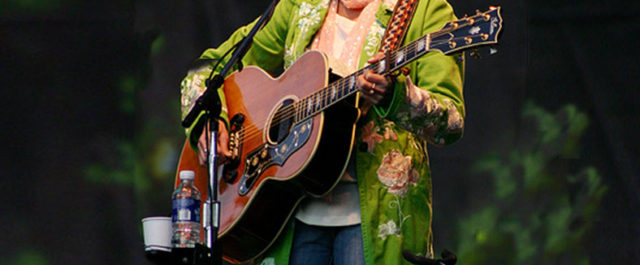

Kathryn Stripling Byer

It took me a while. After all, who wouldn’t want to wear fancy boots, lots of fringe, and sing, not to mention write, songs like “From Boulder to Birmingham”? Even now I marvel at how long it took me to realize that the poetry I was writing was my way of singing. After years of Emmylou envy, I began to hear my voice, as I gave readings, approach song. I began to focus on poetry as sound, as what Richard Wagner came to call even years before he’d inscribed the first note of an opera, “sound landscapes.” Of course this poetic landscape encompasses all the elements of poetry, syntax, image, lineation and so forth, but more and more I began to listen, really listen to where the language was leading me.

This listening can take its own sweet time, and waiting is, as far as I’m concerned, a key component of good writing. Several years ago, while visiting a good friend in Oregon, I joined her and a few of her poet-friends for a workshop. As a prompt, she offered up a poem with a train in it. I can’t recall much of the poem, but the sound of that train pulled me into the first line of a poem that took me a long time to sing to its closing notes. “So long, so long, the train sang,” I wrote in my notebook. And so began the first notes that kept calling and calling to me, haunting me, even down to the final days of my father’s life, as I lay in my childhood bed, trying to weave this poem together, finally. I was, as I now realize, “listening” this poem to completion.

“Legato,” that is what I was trying to achieve–the legato line. Singers know it well, and so indeed do poets, though they may not know it…..yet. The opposite of legato is staccato, and I knew the sound landscape for this poem was not at all staccato. This poem’s legato line was a moaning, all the way down through the flatlands, sounding like Georgia blues singer Precious Bryant singing, “I’m goin’ home on the morning train. That evening train may be too late, so I’m goin’ home on the morning train.”

I was going home, too. I’d been going home since that first line jotted down quickly so many years ago in Portland, Oregon. “So long, so long, the train sang/ deep in the piney woods, well out of sight…. As sound only, it found me…long vowel reaching for nobody I knew as yet,

sounding an emptiness

deeper than I thought could blow through

the cracks of this song where I’m kindling a fire

for my fingers to reach toward,

a kindling that transforms whatever it touches

to pure sound, a pearl, say,

that’s cupped in my palm

like a kernel my teeth cannot crack,

the pulse of it strung note by note round my neck,

that old rhythm and blues beat

I can’t stop from singing me home

on this slow morning train

of a poem, its voice calling

downwind, What took you so long?

This morning train of a poem became the first poem in my most recent book, Descent. And its question still haunts me. What took me so long to give up Emmylou and let go into my own legato line? My own lifeline bearing me home again? Maybe it’s the same journey we take over and over again with each new poem we write.

Kathryn Stripling Byer, a native of Southwest Georgia, lives in the mountains of North Carolina. Her poetry, prose, and fiction have appeared widely, including Hudson Review, Poetry, The Atlantic, Georgia Review, and Shenandoah. Her first book of poetry, The Girl in the Midst of the Harvest, was published in the AWP Award Series, followed by the Lamont (now Laughlin) prize-winning Wildwood Flower, from LSU Press. Her subsequent collections have been published in the LSU Press Poetry Series. She served for five years as North Carolina’s first woman poet laureate.

Kathryn Stripling Byer, a native of Southwest Georgia, lives in the mountains of North Carolina. Her poetry, prose, and fiction have appeared widely, including Hudson Review, Poetry, The Atlantic, Georgia Review, and Shenandoah. Her first book of poetry, The Girl in the Midst of the Harvest, was published in the AWP Award Series, followed by the Lamont (now Laughlin) prize-winning Wildwood Flower, from LSU Press. Her subsequent collections have been published in the LSU Press Poetry Series. She served for five years as North Carolina’s first woman poet laureate.

Photo credit: By Yogibones from (Flickr) [CC BY 2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons